Not So Wild: – Hans-Jürgen Hafner, 2022

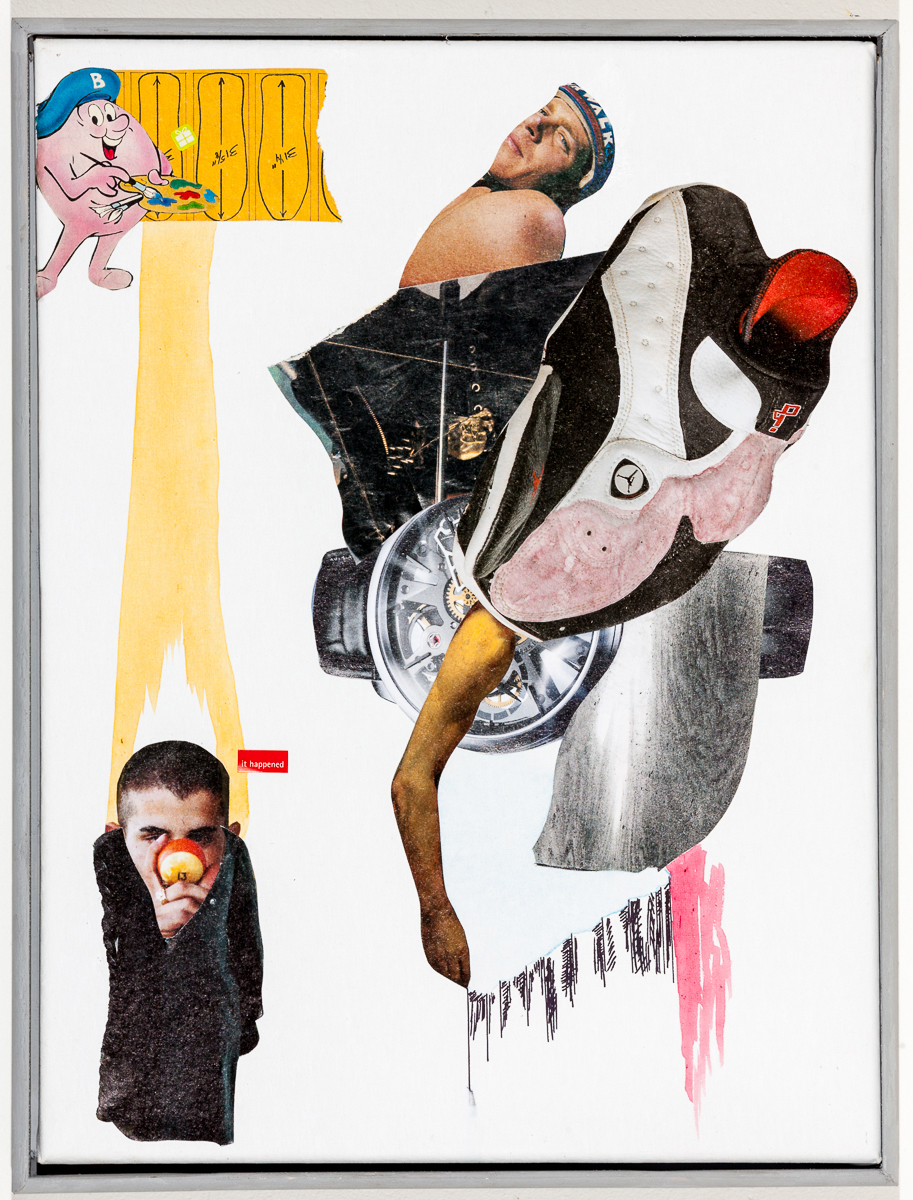

By the end of 2021, the idea that (punk) rock and painting get along well together has become so thoroughly normalized that the only thing worth mentioning is that both—rock and painting—carry their own burdens. It fits that in rock and painting, the supposedly dead persist longer. Whether this is truly an advantage remains to be seen. Right now, authorities are reporting the arrest of Christian Rosa, a fallen star in the world of Crapstraction: his brand of rock’n’roll is painted for models and those who aspire to be models, in the spirit of authenticity. The accusation? Forgery—specifically, works formerly attributed to that old master of punk graphic art and now midcult art star, Raymond Pettibon.

The ease with which we encounter the painting rocker or the rocking painter—be it in the gallery down the street, on Instagram, or on the Sunset Strip—is precisely what’s become taken for granted.

Back in the late 1970s, it was still “wildness” that served as a central term—not so much to bridge music and visual art as distinct arts or genres, but rather to reconcile two forms of practice and production that had been sorted by tradition into “entertaining” (or industrialized) and “serious” (or bourgeois-artistic) categories. Wildness became the final word in a string of final words, posing as a solution to keeping the culturally separated under one roof. The thread linking punk and painting, pop and high culture, lay in the “wild” as their shared, inherent transgressive potential—and “Geile Tiere”, proverbially, was the band project born from this, more “queer” than “rock,” featuring artists known in the art world as the “Junge Wilde”: Luciano Castelli, Salomé (né Wolfgang Ludwig Cilharz), and part-time co-performer Rainer Fetting.

There was no need to panic: that imagined, wild super-art, fusing the best of both worlds—or, in the language of record companies and cultural bureaucracy, fully deploying “crossover potential”—never actually emerged from this episodic blend. Not even when the “wild,” which quickly fell out of fashion, drifted simultaneously toward “genius” and “dilettantism” in consciously or unconsciously subcultural settings, regardless of whether the institutional or disciplinary border between image-making and sound, between art and pop (or “the people”), could ever really be upheld. Economically, though, one thing remains true: many still pay for the few, especially in pop.

The “new spirit of capitalism,” which has swept across the world for some forty years now, cares little for philology and certainly not for history. It is precisely for this reason that today’s discourse on “artistic practice” naturally assumes that anyone working as an artist can—or even must—also engage as a participant in music, ideally playing in their own band as part of an individually branded artistic “project,” framed positively under the rubric of “artistic subjectivity.” Today, subjectivity primarily means acting as a personal brand, throwing literally “everything”—skills, labor, hobbies, ideals, habitus, identity, heritage, even bare existence—onto the frontline as potentially commodifiable resources, whether in the analog or digital worlds. In other words: fully deploying crossover potential.

It would be nice if, in this process, a couple of bucks would come our way, enough to keep the artists’ social insurance happy and to afford the next exhibition participation. It is precisely these societal, economic, and institutional abstractions that are hardly conducive to an artistic life or the individual production and/or exploitation of cultural products—yet the persistent, personal will and capability to make art must still assert itself in opposition. (As a side note: a frustrating, technologically explainable collateral problem is that I no longer need to ask you about your favorite record or beloved painting when the algorithm predicts my question and already knows your answer. Just thinking about this is… cringe.)

Offering an answer to how music and art relate as professional and/or amateur activities—positioned between production/labor and consumption/pleasure—is far from straightforward. Both music and art serve as foundations for cultural commodities that are hyper-coded according to their own logics, simultaneously “unaffordable” and “free,” and notoriously overdetermined as cultural heritage (your taste, my museum, or my playlist). These cultural forms would first need to be tailored in such a way that they can even be meaningfully engaged with, without inevitably collapsing into mere posing from the outset.

Notably, the attribute “wild” does not come to mind when I look at Benjamin Novalis Hofmann’s paintings, which almost surprises me in a guy who, on one hand, references Novalis—certainly not the krautrockers—and, on the other, frequently sports Motörhead T-shirts. Rather, what I encounter in his work is a sense of construction, assemblage, perhaps even syntax—a reading further reinforced by considering his image series and bodies of work that unfold over extended periods.

Absent too is the calculated or tongue-in-cheek embrace of “badness” as a more or less successful translation of punk’s (rock) musical subversion and cultural negation into “bad painting.” Yet these paintings do not shy away, emphatically, from being “painting” and from asserting that painting, when successful, is both a deeply material act and a generator of image and art—even if that doesn’t automatically guarantee interesting pictures or good art.

Although these works are overtly paintings, they do not seem to appeal to a “taste” aligned with the genre—neither materially, conceptually, referentially, nor discursively. Each image, despite the serial work, formal or semantic coherence, and the context of the larger body of work, stubbornly points back to itself, repeatedly attempting an “escape from Alcatraz” without ever shedding its inmate uniform. This is a form of art, because painting is a historically and institutionally fortified prison, supported not least by substantial funding, from which it is difficult to escape—even through deliberately bad or consciously anti-painting gestures. The guards watch closely.

At the same time, these works elude the two interrelated frameworks that define painting’s status within the continuum of so-called “contemporary art.” One framework concerns art’s contemporaneity—not merely as representation but as production in the broadest sense—within which painting as a practice competes with other multimedia, performative, participatory, or activist practices and is comparatively less “urgent.” Its well-documented longue durée as an image medium inside and outside of art can even feel disruptive.

The other framework pertains specifically to painting’s role as technique, genre, and image medium within the contemporary, and how painting, when consciously “painted,” exploits this fraught position while simultaneously asserting its claim to be art.

Overall, Benjamin’s paintings do not trade on “wildness,” “rock attitude,” or “badness.” Rather, they pursue a highly disciplined and direct engagement with subjects such as landscape, figure, and veduta—approaching these themes, to some extent, in an academic manner. This sensibility is further reinforced by his serial methodology, which both solidifies and liquefies pictorial ideas and processes, moving, so to speak, from the (combat) star to the figure, from landscape to nugget.

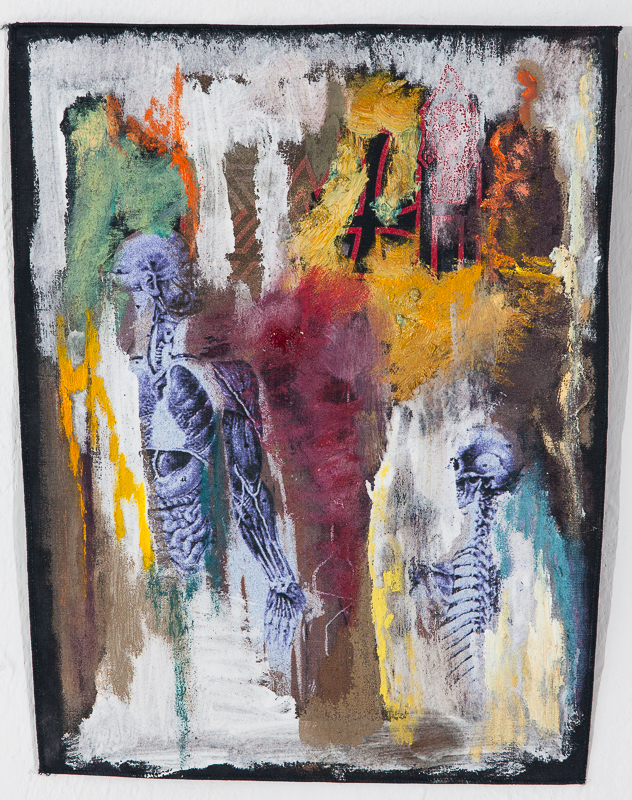

Particularly where painting manifests in its purest, gestural form—such as in the series of format-bound “Patches” (2013), whose compositions are strictly determined by the dimensions of fan patches popular in heavy metal culture, bearing band logos, cover art, and the like—we encounter the clearest references to popular music cultures, even as they remain embedded within painting itself. This takes place through a painterly approach both rigorously controlled and conceptually calculated, inevitably reflecting back on the medium’s tools: color and application, gesture and motif. The explosively graphic-art motifs of patches from bands like Death, Iron Maiden, or Slaughter are simultaneously thickly painted over, colorfully countered, and finely dissected, with letters and skeletal fragments floating to the surface—resonating with the musically and symbolically constructed counter-worlds that metal and punk have circulated, especially since the late 1980s in extreme mutations like death metal and grindcore, caught in ongoing tension with their either excessive or insufficient cultural-industrial reach.

This also serves as a reminder that discipline—undoubtedly required in extreme measure to unleash oneself properly during, “Regurgitated Guts” off Death’s seminal album “Scream Bloody Gore” —and transgression are by no means mutually exclusive, while Geile Tiere have always been comparatively easy to come by.

Hans-Jürgen Hafner

[translation powered by DeepL and A.I.]

Aesthetic metabolisms – Raphael Nocken, 2022

For the past twenty years, Benjamin-Novalis Hofmann has been cultivating a repertoire of motifs and developing bodies of work that weave allusive references and render the traditional division between abstraction and figuration increasingly untenable. It is therefore challenging, when considering a text that spans nearly two decades of his artistic production, to avoid falling into descriptive or stylistic categories that offer only tenuous footing—categories that risk overlooking or excluding critical aspects and ultimately fail to do justice to the complexity of such an expansive oeuvre.

For this reason, it is more productive to step away from seemingly stable yet relatively narrow stylistic labels: bad painting, abstract painting, representational painting, or painting liberated from present concerns—what fresh, original perspectives could these terms really offer on Benjamin-Novalis Hofmann’s work? Perhaps it may be useful for quick classification to know if the artist aligns with post-representational painting, but such banal terminology hardly inspires genuine interest in engaging with the artist’s aesthetic thinking or probing the substance of that thinking beyond language—the “thinking in other media.”

From this reflection emerge the following observations, which focus exemplararily on a few selected series, since the diverse body of Benjamin-Novalis Hofmann’s work ultimately weaves intricately and skillfully together across multiple strands.

What is readily apparent is the artist’s pronounced interest in the geological: matter, dust, soil, and minerals. The Interstellar series features expansive, blurred pictorial fields punctuated by round forms that emerge from the depths—suggestive of planets, perhaps distant stars. These are abstract formations rendered in richly shifting colors, allowing if anything only faint allusions to landscape. They evoke mineral-toxic soils that conceal something other, something indeterminate. Are contemporary environmental catastrophes being alluded to here?

Though the series titles resonate with dystopian potential, it would be misguided to ascribe a dystopian vision to the artist’s work. Even well into the 21st century, scientific inquiry continues to grapple with the fundamental question of how matter became biologically alive—and revisits the question of life’s origins with renewed rigor. It is difficult to pose the question of biological origin when no singular, determinate beginning ever truly existed. How might one fix such a moment, which was never just one moment, whose origin cannot be pinpointed in a definitive temporal frame, understood as a discrete, measurable event? Rather, life’s emergence is better conceived as a phenomenon of indeterminacy, motion, and multiplicity. Life arose in many places and at different times, possibly even within mutually isolated systems.

One critical aspect of geologization is recognizing what is called geological life—that is, the mineral dimension embedded within the human constitution. Indeed, all organic bodies—whether human, animal, plant, fungal, or bacterial—are deeply entwined in the geological-mineral system through their metabolic functions and evolutionary ancestors.

In Benjamin-Novalis Hofmann’s work, color conglomerates that form the “earths” seem never quite settled on how to assume a finite shape. The colors remain perpetually coiled, smoky, and indefinite; interlocked but never fused or blended so as to form a coherent mass. The indeterminacy of the mineral, of color itself, constitutes the very essence of these works. This “obfuscation of the reified color mass” recurs throughout his series.

Both UTOPIA_LOST_IN_CHAOS and the FUTURE_EDGELANDS series—note again the beautifully dystopian tonalities of these titles—feature bold, radiant applications of color that are, however, blurred and separated by painterly interventions at their edges. The colors must share the precarious picture plane, closely interwoven yet isolated. What do we actually see—wild color clouds (UTOPIA_LOST_IN_CHAOS), or tightly, vertically abutting layers of paint (FUTURE_EDGELANDS) that simply exist without any evident attempt at form-making?

Sometimes blurred softly along the edges, sometimes sharply wiped with a swift brushstroke, the painting becomes a sedimented force of earth history—becoming, in effect, a geological act.

Benjamin-Novalis Hofmann’s works evoke events of recent decades, particularly their visual traces as disseminated through photographs and video media, portraying a world marked by planetary catastrophes. A multiplicity of disaster images converge to form a new aesthetic field—an iconology of the Anthropocene. Within this corpus, one encounters vast, global, and indelible forest fires; marine dead zones where life is no longer possible, visually marked by swarms of dead fish floating on the sea’s surface; oil slicks and burning landfills serving as visual ciphers of industrial devastation; emerging pandemics that impose transformative pressures worldwide with long-term consequences.

These new visual and experiential spaces of the world pose radical challenges to the cultural self-understanding of industrial societies and their relationship to the “unthinkable world,” especially nature. In doing so, they continually demand reflection “on humanity in relation to its real, hypothetical, or speculative extinction.”

That Benjamin-Novalis Hofmann’s compositions become increasingly dissociated from concrete objects in our reality is evident in the works from the two series SPIDERMAN and SILVER SURFER. The artist presents the figures from the Silver Surfer and Spiderman series isolated in space, placing them against empty or monochromatically colored fields. A synthesis between pictorial space and figure only gradually emerges throughout the series. In preliminary stages, organic proliferations anchor figuration within the pictorial field.

A defining feature of this antihumanism is the overcoming of traditional portraiture, resulting in a total negation of the human as personality—in contrast to the object. The wildly expansive compositions concentrate compositionally on the center of the image, with little emphasis placed on the densification of paint matter. Hofmann generates a powerful chromatic tension through his use of black and red, dominating the entire pictorial structure. This tension is also apparent in the manner of painting: at times, the brush is laden thickly with oil paint; at others, the brushstroke is barely perceptible.

Even more pronounced is this tension in the act of painting itself: Hofmann physically engages with the canvas. He presses the brush forcefully into the surface, causing paint to push out along the edges of the brush. He scrapes and scratches away paint; fingerprint and tube marks remain visible. This vigorous technique produces a dynamic energy throughout the work. The entire composition seems alive, in perpetual motion.

Upon first encountering the Spiderman series, the viewer instinctively associates the imagery with the human body. Yet the question arises: does Hofmann truly depict a humanoid? All defining human features are absent; there are no fixed boundaries—neither in color nor form. Rather, Hofmann appears to have created a new reality. The notion of an organic humanoid is recognizable and intuitively associated by the viewer, yet the artist has not rendered a likeness of reality, but rather a being related to the humanoid. The image as a formerly representative pars pro toto of the world is constructed here as something autonomous and self-legislating.

Formal elements are fragmented, and the figure is not clearly delineated in a mimetic sense; the formal means find no referential anchor to objects that would allow for identifiable forms. Instead, the graphic tools independently generate new formal structures. The image thus detaches from its object, revealing natural analogues within the body’s basic form. By intensifying the reality effect of his images and foregrounding the mineral-organic nature of his pictorial inventions as the essence of his aesthetic metabolism, Hofmann creates compositions of striking presence and power.

The work of painter Benjamin-Novalis Hofmann presents itself as, in the best sense, a hermetic oeuvre—distinguished by its aesthetic rigor, artificial pictorial aesthetics, religious-philosophical dimensions, and the indeterminacy of its meaning. The questions he revisits time and again unfold not through linear or rational sequences, but as assemblages—ensemble-like compositions of visual and acoustic impressions that are diverse and variable in their interpretive depth.

Analogous to Walter Benjamin’s writings, one can discern in Hofmann’s depiction of different natures—both the primordial mineral nature and the secondary human nature—complex relations between natural history and allegorical form. For the viewer, the pictorial fields marked as image-spaces and inhabited by mineral and organic forces constitute the arena in which the boundary to the world-without-us can be experienced in its terrifying yet seductive dimensions. Norbert P. Franz names this the Tremendum and the Fascinans. These elements make possible the experience of the numinous, which precisely consists of these two ingredients: the Tremendum and the Fascinans.

In this, one aligns with Eugene Thacker’s assertion that “the numinous is the liminal human experience in confrontation with the world as something absolutely nonhuman, the world as the ‘wholly other,’ that which remains in the unspeakable mystery beyond all creatures.”

Raphael Nocken

[translation powered by DeepL and A.I.]

In his paintings, Benjamin-Novalis Hofmann stages an existential struggle over the world of painting. Abstract or figurative, colored or colorless, glossy or matte—often all at once or in juxtaposition. These are probing questions posed to painting itself, and ultimately, to the artist’s own practice.

At this provisional stage, Hofmann presents an ambitious transcendence of conventional painterly boundaries and genres. Motif-wise, he offers us iconographic puzzles to unravel.

His titles, drawn mostly from literary fragments—poems or novels—pose a question: do they serve to explain the images, or do they simply open further interpretive layers within his pictorial world? The question is ultimately ancillary, for it is Hofmann’s painterly obstinacy that clearly dominates. Here lie the true qualities of the work.

Hofmann does not merely absorb painterly tradition; he recombines it, turning the combination into a montage. His painting is so densely layered that one suspects he deliberately resists producing a homogenous or consistent oeuvre.

Yet it is precisely in this continuity of effort that a remarkable coherence emerges, providing a shared denominator for all phases and dialectical leaps of his practice. This stance of painterly inquiry betrays a certain hubris and obsession. His drive toward sublimation, focusing intently on painting, results in works of striking independence.

Within a single image, Hofmann approaches all other images simultaneously. Perhaps initially conceived as a compromise, his painterly layers evolve into an autonomous work.

Color dominates above all. Often screamingly intense, it contributes alongside formal variations to holding the tension within the image. The works are extraordinarily alive in their effect.

In pursuit of a distinct aesthetic entity, Hofmann has embraced the question of all or nothing—ultimately choosing everything.

Peter H. Forster – published in:

„Bis ans Ende der Welt“, Verlag Revolver

[translation powered by DeepL and A.I.]